The long tail of war keeps going

For those that have served, and those caught in the crossfire, it never really stops

I think that for those that haven’t experienced it’s hard to explain what I call the ‘long tail of war.’ I deployed to combat zones four times in my 22-year Army career. First, in 1990 for Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm as a scout pilot and platoon leader. In 2003 I headed to Iraq for the initial invasion as the Operations Officer for a UH-60 equipped combat aviation battalion with the 101st Airborne.

Once settled at Q-West airbase in Ninewa province I handled civil affairs working with the local villages in our sector. Two more tours as a public affairs officer with the Multi-National Security Transition Command followed in Baghdad in 2005 and 2008 followed before I retired to let it all go.

I have many fond memories of Iraq. While it was war I was blessed to spend time with the local people. Share food, learn about their hopes, help facilitate projects to improve their lives. I hugged their kids, bounced their babies, joked about their lives. The circumstances that brought me there were awful but I believed I could carve out the best of it if I just tried to improve their lives and bring all of my soldiers home.

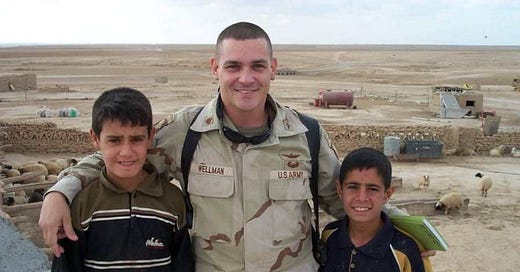

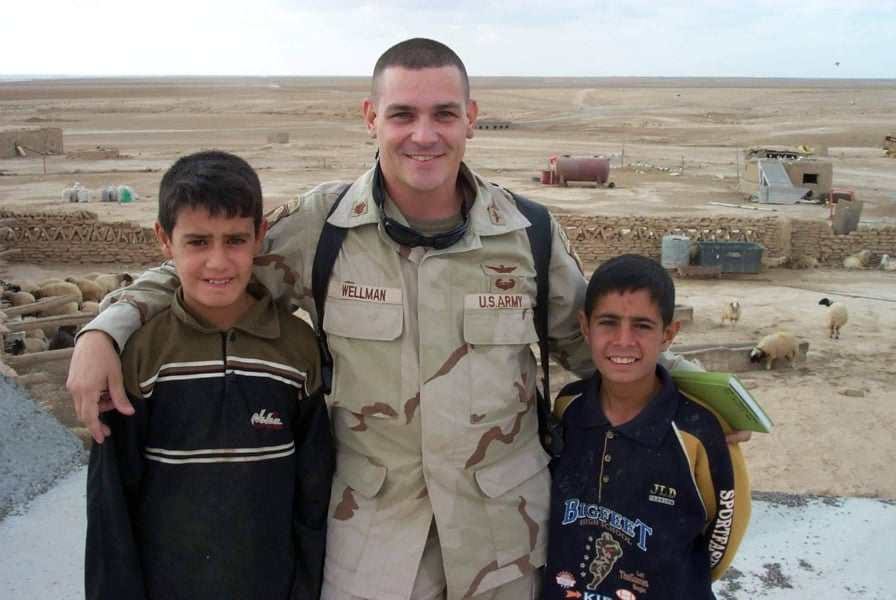

Here is one of my favorite pictures from that first tour in Ninewa province. It’s near the end of the tour as we are in full swing building new projects in the village. The kids of the village wanted pictures with me often.

My tours weren’t too bad. I never got “blown up” or wounded beyond silly physical mishaps and injuries associated with being in a cockpit for countless hours, careening around in a Hummer over broken roads, and wearing body armor all day. But the long tail of those experiences touches me to this day in my mental health, physical disabilities, and the connections I maintain to those I served with, and served directly, in Iraq and around the world.

Recently that long tail touched me unexpectedly and brought me back down to the emotions and reality of war not just for those of us in uniform but our families and those who were on the other side of the coin in the Iraqi villages, cities, and fields we invaded.

If you’ve read my previous post’s, you know that I have long maintained relationships with those I met in Iraq in the main village that was my primary partner in 2003; Jeddalah Sofla. It’s a dusty little farming village just a couple of kilometers from the western perimeter of the air base that had been a critical launching point in Iraq’s war against Iran, a key location for our U.S. efforts and again in the later fight against the Islamic State until even today.

I am connected on Facebook and other social media channels with probably a dozen of the villagers who knew me when I was there 20 years ago and a new generation that has followed even and heard of me through their fathers and uncles. It is one of my great joys hearing about their success, struggles, or reminiscing about those old days and the wonderful men I came to know.

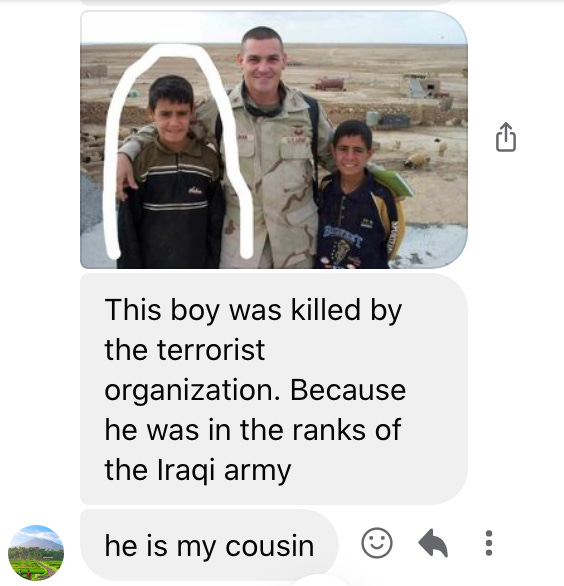

Then sometimes you get a simple message that cuts to my heart. Often, they are just a simple few sentences that brings back the horror of never ending suffering that follows war for both sides of the fight.

I got that one about two weeks ago.

One of my favorite pictures with a line around one of the boys. He’s dead.

Cuts to the core

I’ve been thinking about it since. That young man under my arm is named Mahmoud. He was literally the first Iraqi child I ever met. He and his father were picked to do one of the most dangerous things imaginable in May of 2003. They were asked to walk the seven kilometers from their village to the newly established “gate” guarding the just arrived U.S. Army soldiers and their helicopters to make contact with the Americans.

How could that be dangerous?

To start with, we had a lot of guns and a lot of tired and nervous fingers on the triggers. Many of my fellow soldiers were on edge after the exhausting invasion that had us moving all the way from Kuwait to the furthest northeast of Iraq in just three weeks with little sleep and a new mission, we had only just received, to occupy this sector. Walking up to us unannounced could easily be a death sentence for those that risked it, yet they came.

They brought a note from Dr. Mohammed, the sheik of the village, asking for help with water that they used to get from the base, and a stop to the use of a range that our counterparts in the infantry had hastily established on the perimeter that faced their village. It appears they didn’t know the village was close enough that more than a few stray bullets finding their way into the walls of their homes.

You know…typical stuff.

Meeting at the gate

I went out with one of my pilots who had formerly been an Arabic interpreter and got more details and arranged a follow-on meeting to coordinate our answer and a possible visit. The rest is history as they say. After a brief disagreement with my higher headquarters counterpart, we began a relationship that would bring us friendship and security and for the villagers both improved lives and, in many ways, worse ones over the decades to come.

We would build a clinic and a school in the village while I was there. Eventually a large chicken house and other facilities. They would find jobs as interpreters or other opportunities with the Americans and Iraqis, but it also brought targeting from those who wished to do us harm.

Eventually, they would plant a bomb in the road outside the village and Dr. Mohammed would lose his legs in the explosion. I fought to get him treatment in the U.S. hospital in Tikrit from my desk outside the Pentagon.

Then, in 2011, Mohammed would die in the clinic we built for him. Assassinated by men acting as patients but concealing guns.

War comes again

Then the Islamic State struck in the spring of 2014 and eventually the entire region fell to their despotic rule. Most of the villagers fled the area as they were targeted by the extremists due to their close relationship with the United States when we were there. Many of the young men joined the Iraqi Army to fight back.

Young Mahmoud was one of them. He lost his life in battle on April 15th, 2015 as ISIS expanded their campaign in northern Iraq to expand their caliphate.

Why them?

On one of my first visits to Jeddallah Sofla in May, 2003 I asked Dr. Mohammed why they sent the old man, Abu Mahmoud, to our gate. It was a long walk after all and he was in his 70’s at that point.

He replied, “Well, he is old and already has many sons.”

I was a little take aback and laughed. “So, you’re saying he was expendable.”

“Yes,” he replied. We laughed. It was one of my first lessons in Iraqi culture.

So, then then did they have his youngest son go with him? Well, they figured maybe we would be less likely to shoot if there was a kid. I suppose they knew us pretty well.

The young man I was chatting with on Facebook told me that Mahmoud’s father still lives. He is 95-years old now. He remembers me as a man of honor who kept his word.

I’m not sure I’ve had a better compliment in all my years of service.

The long tail of war doesn’t really end for those who serve, those who lived in war, and those who survive. Not here and not there.

Update:

Thank you for being part of my community. Our new videos interviewing Democratic candidates for office are doing really well on MeidasTouch. I hope you’ll watch them on this playlist.

Mike Flynn’s lawsuit against me continues. He has now filed for a stay of our case while he appeals the dismissal of his defamation case against Rick Wilson in Florida state court. We will be filing a motion to oppose and get this over with. All of this is designed to drag it all out. I’d love your support for my legal defense fund if you can help.

Thank you for your service and for all you are doing now too. I contributed to your legal fund and wish you well.