Sunday Read: Ranger’s got a plan

The lessons I learned as an 'old' Ranger student that carry me still

Get up the hill

Sometimes the chip on my shoulder leads me to the strangest places. This time it was the bottom of a ravine in the Blue Ridge Mountains outside of Dahlonega, Georgia, only about a thousand feet from the Appalachian Trail.

Well, technically about a thousand feet below the Appalachian Trail.

It was pouring rain as I lay in the mud contemplating if I could eat the fresh ferns growing in front of me. Eating just one meal a day for five days was starting to eat away at my belly and I’d already learned fern shoots had a nice crunchy feel to them. Our platoon was stuck in this growing puddle as the young, brand new Second Lieutenant then in charge of 30 Ranger School students struggled to figure out where we were, and where we were supposed to be, surrounded by increasingly angry Ranger Instructors.

Then I heard the fateful call. “Ranger Wellman…you’re the new platoon leader! Ranger Jones…you’re platoon sergeant!”

Dammit.

We were both two of the oldest and most senior Ranger students. I was an Army Captain at the time with almost six years of service, three platoon leader jobs, multiple Army schools, and a combat tour under my belt. That made me the ‘old man’ of our class where we didn’t wear rank, but everyone knew who everyone really was out in the world.

When the old guys got the hook in the middle of a patrol, it’s always a sign they want someone to get shit done. Running over to the Ranger Instructors, they laid it out quickly. “We are 20 minutes late for our hit time and at the bottom of the mountain we are supposed to be on top of. Get this platoon moving or you fail.”

Jones was a Staff Sergeant out in the regular Army world, so we were two of the highest ranking people in the class. We walked away and agreed the best way was to simply go ‘high diddle diddle…right up the middle’ and just get everyone moving uphill immediately and figure everything else out when we get out of this hole. He would lead up to the top and establish a rally point. He will go right to kick people into gear, and I’ll go left. See you at the top. Go!

I started working my way around the circle booting guys in the ass and saying “Follow Jones up the hill. Meet you at the rally point. Move!” As I’m running from man to man, I feel myself bodily lifted from behind by my giant ruck sack.

I turn around to find two huge sergeants with their signature soft patrol caps and Ranger tabs on them looking at me. “Ranger what the hell are you doing?”

I was tired, wet, a month and a half into this exhausting ordeal, and in a hurry. “Well, Sergeant I’m trying to get these assholes up that hill and if you’d leave me alone for a minute, I could get it done.”

They looked at each other. Turned to me and offered the words that would become a lifelong mantra of mine, “Ranger’s got a plan. Carry on.”

“Thanks.” Up the hill we went as they started throwing mortar simulators to help ‘motivate’ the platoon. We struggled to the top where Jones had everyone fall into a secure perimeter. I gathered the squad leaders to plan the rest of the patrol which was to be an assault on a ‘guerilla camp’ about three kilometers away.

Quick plan and we moved out in proper order back on time. Not long after came the magic words, “Wellman and Jones, you’re relieved.”

That’s a ‘go at that station’ and one of two patrols I had to pass for mountain phase under my belt. Success.

Record scratch “Yep…that’s me. You’re probably wondering how I got here”

I used to get asked a lot how an Army Aviation officer who flew scout helicopters after graduating West Point ended up at the premier infantry leadership course as a mid-grade Captain? Simple, I had a chip on my shoulder, and it got me in over my head once again.

After leading a scout helicopter platoon into Desert Storm I returned to the peacetime Army looking at what lay ahead in my career. I was promoted to our Apache battalion’s staff to serve as the Intelligence Officer. Not the greatest job but getting a ‘primary staff position’ as a lieutenant was a feather in my cap. Next, I wanted a transition into the Apache and a company command, and the fast track was all mine to ride to glory.

Shortly after getting my shop organized and implementing a host of training and improvements a new young Captain arrived at the unit. He hadn’t deployed to Desert Storm because he had been stuck at Fort Rucker while going through flight school. Since he couldn’t join a unit, he managed to go to every school imaginable.

He did it all. Apache, Air Assault, Airborne, Pathfinder, Ranger, and obscure schools you’ve never heard of. But no combat patch on his right shoulder. My battalion commander, a great guy by the way, got his officer record brief during a staff meeting and was just gushing. “Wow, look at this list. Here is our next company commander!”

Wait…what?

Overachievers Unite!

I had already led not one, but three scout platoons, including in the final battle of Desert Storm. Had a couple of schools under my belt and had been in the unit for two years. But all those badges leaped him up the list.

I was the last of four kids of a New England father and Italian immigrant mother. My siblings had all been leaders in whatever field or sport they chose. So, as number four, whether I knew it or not I had to overachieve. I took that mission to heart. Student council, class officer, captain of the swim team, West Point, flying –– you name it, I over-did it.

Fun sidenote: on top of PTSD and survivors’ guilt, I also have some lingering mental health issues from my childhood. Shocking, right?

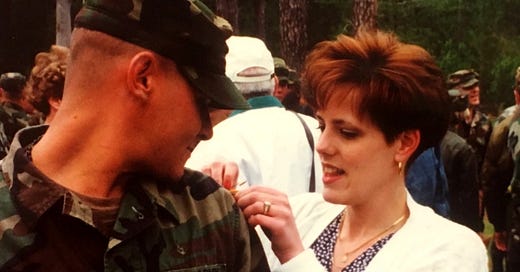

I came home and told my wife my grand plan. If he can do it, I can do it. So, I updated my assignment ‘dream sheet’ on the spot. I wasn’t going to the aviation branch Captain’s school, I was going to the armor branch one. I wasn’t going to be a ‘leg’ anymore, I was going to Airborne school. Oh, Ranger School is now open to non-Infantry officers again, well, let’s put that on there too. How hard can it be?

Once again, I would discover something was in fact really hard.

I won’t bore you with the details but a year later sitting at Fort Knox the assignment officer made a host of mistakes and called to apologize by telling me the good news that he actually had a Ranger School slot for me.

There is a term “hoist with his own petard” that comes from Shakespeare that refers to a bomb maker being blown up by his own grenade. I was super hoisted.

I had some classmates who were training to go the Special Forces Qualification Course and were already Rangers and they offered to get me in shape, trained, and prepped for the course. There were no airborne school slots so I would go to Ranger School as one of thirty ‘leg,’ non-parachutist qualified students, in our own platoon that would start Ranger Class 93-3 in January of 1993. Only two of us would graduate about a hundred days later.

Opening doors

Ranger School was a game changer for me in a million ways. It taught me invaluable lessons in leadership that I wish I had known before leading men in combat the first time. It showed me just how much could be taken away from you and still be capable of functioning and leading. It taught me humility as my rank was stripped away and I found myself regularly taking orders from privates right out of basic training assigned to one of the three Ranger Battalions.

I often say that having that Ranger Tab on my shoulder opened more doors and evened out more expectations in my Army career than my West Point ring ever did. I was assigned to Fort Campbell as an Apache Battalion Acting Operations Officer after graduation. We supported the famed 3rd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, the 187th Infantry Regiment ‘Rakkasans.’ When I walked in a mission planning session, they saw my Ranger tab and knew I understood what an L-shaped ambush was and where a support by fire line would be and how they would be moving on the objective. We shared a common language.

When my first wife was killed in a car accident a year later while seven and a half months pregnant, I laid in bed alone and thought I’ve got food, a bed, and a roof over my head. I will get through this.

Ranger School gives you a ‘level of suck’ that is unmatched in peacetime training like few other schools available to average people. It gave me that. Being Ranger qualified gave me a lifetime of skills that I still tap into regularly. I never served in a Ranger unit, but that tiny slip of cloth has carried me through a lot of tough times.

A voice in the dark

The next night after that mission in the ravine, we were moving quietly along the Appalachian Trail in a long line on the way to another ambush. I was in the trail position covering the rear of our platoon with the Squad Automatic Weapon. We had passed one of the lean-to like structures dotted along the trail for hikers to shelter in for bad weather and over night.

Out of the darkness I heard a woman’s voice. “Are you soldiers? I need help.”

I called a halt to the patrol, and everyone took cover positions and then sent word to have an Ranger Instructor join me at the back of the line. We found a lady in soaking clothes looking desperate. She and her daughter were hiking the Appalachian Trail and the young teenager was in agony with gut pain that she suspected was her appendix. They had heard us the night before and were hoping we would come their way.

Those incredible Ranger School non-commissioned officers swung into action. They quickly organized our students into a litter team and called for an Army Medevac aircraft to meet us at the next break in the trees. We carried the girl about a kilometer where she and her mother were lifted out of the mountains and taken to a hospital in town.

We watched them leave, feeling good about our service for a minute.

The RI’s screamed at us, “What are you doing?! Get back on mission! We’re late because of all of this dicking around!”

Back in line. Back on mission. We had a job to do. We shook it off and went to work.

Every time I’ve had a setback in life, and I’ve had a few, even lately, I remember those two days of Ranger School and the lessons I learned.

• It can always be worse

• You must recognize that and carry on

• There is always time to help others

• Don’t let the chip on your shoulder get you into trouble

Okay, I’m lying. I’ve never learned that last one. I keep letting the chip on my shoulder get me into situations I should have avoided. It’s worked out well, for the most part.

Authors Note:

I hope you are enjoying the ‘On Democracy with FPWellman’ Substack community. I would really appreciate you considering upgrading to a paid subscription. We will be kicking in paid subscription exclusives in just a couple of weeks and I don’t want you to miss any content or opportunities. Your support allows me to focus on telling the stories of our democracy, interviewing smart people, and helping those in the fight.

If you haven’t heard our podcast is now part of the Meidastouch Network and will premiere on Friday evenings at 11:00 PM EST/8:00 PM PT every week. Here is the latest conversation with former CIA officer John Sipher.

Enjoyed this very much. My long(relatively)long life has been surrounded with military, either family or friends. I’ve lived my life not far from the vaunted AT as well as a few other fun survivalist areas. I also listened to your podcast. I’m a paid subscriber because I believe in your message and your current mission. Keep up the good work. GO NAVY!

Somehow this came up at the top of my feed this morning, and after two weeks of complications after surgery was just what I needed. Seems there is no such thing as coincidence. Thank you.